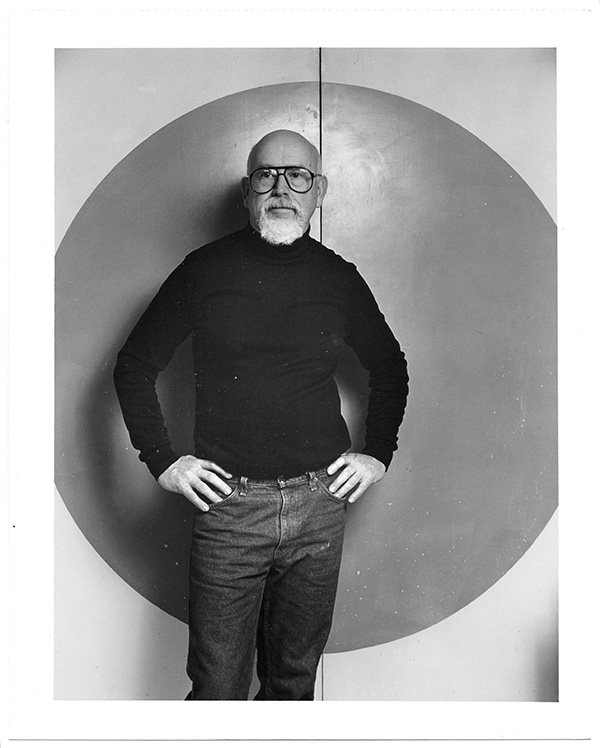

Remembering John Stephenson

SP has adapted the following essays from speeches given at John's Celebration of Life on December 5, 2015, in Ann Arbor, Michigan, by Georgette Zirbes, Paul Kotula, Susan Crowell, and Marie Woo; images are courtesy of Susanne Stephenson, and poem by Debbie Thompson.

Georgette Zirbes

The life of an artist is one of constantly setting priorities in order to keep one’s work, the process of making art, at the center of life, and everything else in perspective in relation to this center. John Stephenson made his art the spiritual core of his personal and professional life, as seen in his family relationships, his home and studio environment, his teaching at and deep commitment to the Stamps School of Art & Design at the University of Michigan, and in his ongoing interactions with the greater community of artists—regionally, nationally, and internationally.

I was fortunate to share in his process for some twenty years as John’s colleague in the ceramics area of the Stamps School. I have always had the utmost respect and admiration for John’s commitment to art as fundamentally central to his life and work. The ceramics program developed as an active, vital, and contributing one, within the school and in the larger ceramic art community, in large part because of John’s energy, vision, and hard work.

He understood that if an educational program is to stay alive and vital, there must be continuous valuation and change. He knew from personal practice the necessity of individual direction and pacing in the process of learning and becoming an artist. He showed patience with students’ needs and an intuitive sense of timing for the appropriateness of nurturing support or sharp criticism. The longevity and visibility of his reputation as an artist and as a mentor attracted graduate students to the program. His teaching process was directed not only toward helping students become mature artists but also toward helping them become mature human beings. Throughout his career, John exhibited belief in the education of an artist in its highest and purest form – and faith in the working process. He was an inspiration to many students, who have gone on to become highly contributing professionals.

Life in any ceramics studio is an ongoing process of negotiations, inspirations, evaluations, assessments, and implementations, all with the primary goal of creating a supportive working environment for those who are involved in the art-making process. As John and I worked together to refine our ideas, processes, and expression as individual artists, we confronted the nature and needs of a community that allowed for both differences and similarities. We often agreed, and we often agreed to disagree. We worked together in synchronization, and we danced around each other in order to work separately. I came to understand the usefulness and timeliness of an Iowa sense of humor. Our process was both linear and circular and sometimes tangential.

Over the many years, I experienced John’s positive energy as he continued to see the possibilities in situations of improbability and chaos, while holding on with conviction and patience to the larger goals of the studio community. John’s artistic career is outstanding in its accomplishments as well as in its sustained vision. What may not be so visible is that John’s unique nature combined talent and focus as an artist with a generosity and gentleness of spirit as a human being, qualities that do not come together often in one person. He was able to keep a perspective on the importance of his working process and at the same time offer information and assistance, generously and willingly, to others.

Paul Kotula

I often recall the generous and soaring space that is the studio at 4380 West Waters Road in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and how the smell of clay, damp or wet, faintly or strongly, permeated its volume, if the breeze did not temporarily perfume it. There, shelving and sturdy tables covered with work – finished sculpture, rough studies, forms awaiting final resolution – punctuated and ignited what was a rather simple, muted interior, with the exception of orange paint shaped precisely on one wall. At any time, there might have been a structure suspended from the ceiling, clay clinging to metal, a complex axial rotation looking like swirling water or an auger still wet with unearthed mud. There may also have been a series of geometric wooden structures pressed with clay, forms moving outward from it like the start of a post-Brutalist subdivision or the chewed remains of an apple harvest.

This was John’s section of the studio that he shared with his wife, Susanne. Here John engineered forms that the world hadn’t known before and that the ceramics world has yet to fully awaken to. Like Alexander Calder and all those geniuses called tinkerers, John used his studio for play and invention, in a most dedicated, serious, and intrinsically personal way. I remember John stating that it was his obligation as a professor at a Big Ten, research-intensive university to do just that. A man with his curiosity could not have done anything else.

John was a risk-taker, an explorer, an innovator. As I recall his many exhibitions, but particularly his retrospective exhibition at the University of Michigan, I am reminded that so much of his work bites at the core of who we are, what we know, what we’ve seen. His abstract sculpture will leave its mark on the twenty-thousand-plus year history of ceramics. It is already in history books and in important collections worldwide; it has been honored by institutions, such as the National Endowment for the Arts.

His surfaces will be noted, too. John often used terse, sometimes even sour-colored, thickly applied skins of slip and glaze not only to shift our perception of his own forms but also to expand our understanding of what nature can produce, especially when influenced by culture. John’s work was astutely formal and heralded new painterly concerns, yet it also called attention to political and social issues. John had great concern for the environment, and much of his work venerated nature’s beauty and power while simultaneously revealing its eminent vulnerability. In that sense, it also addressed the essence of what we are as human beings.

I remember a form that John created using one of his signature removable metal armatures. It was inspired by the baseball, an object with a solid center wrapped in yarn and covered with two pieces of leather stitched together. John imagined what this sphere would be like if it had a flexible volume and were pitched into the air at lightning speed. John’s armature followed the line where the leather strips met. It was made of interlocking piping that could move in tandem until the “right” movement was made visible and secured with screws. With this design, John created a slightly compressed ovoid structure in clay, which he covered in simple, yet gestural markings in deep and rich shades of gray. The form has no defined bottom. Instead, like a baseball, it rests on a point along one of its continuous curves.

The sculpture reaches up and outward into space, while simultaneously being pulled to the ground on which it rests. Only roughly twenty-four inches wide, the work feels monumental. A realization of John’s imagined ball, it is also more than that: it is an affirmation of life. It reminds us that when two things are bound together they retain their connectedness even through the most extreme circumstances, as long as they move with each other. It also affirms our groundedness; as much as we are surrounded by the vast space we call the universe, we are indeed connected to the earth.

When I think of John, I also think of Susie. They were like that baseball, two parts connected, always moving with each other, through moments of immense joy – most importantly the birth of their daughter, Tara, her marriage to Dennis, and the arrival of grandchildren Charlie and Emma – but also through times of intense struggle. That Susie sustained John’s life, repelled the forces of his illnesses, and accepted that many times she must also work with those forces, is a testament to what marriage meant to them.

I learned of John Stephenson the moment I began my studies in ceramics. I think all

students who studied ceramics in Michigan did. As a noted artist, professor, and head of the Division of Ceramics at Michigan, he was the nucleus of an ever-expanding and transformative community of Michigan artists and educators working in clay. His reach was national and international; his exhibition history alone shows that. But John Stephenson also influenced many generations of students, students who have subsequently become noted artists and educators across the country. John’s outlook on ceramics embraced diverse cultures, particularly those of China, Japan, and South Korea; he celebrated the lives and creative spirit of the many people who shared his passion for it.

John was a quiet man with enormous presence, whose heart was always generous and whose imagination soared. We are lucky to have been so close to John, to be near his genius, to be called a friend. He touched more than the earth at the Waters Road studio. John touched the hearts of all of us, and like the clay that records every action of its maker, his impression will always remain embedded within that very place that knows love.

Susan Crowell

In an interview a couple of years ago, the oceanographer Sylvia Earle said, “If everyone could just realize how special it is to be alive on this little blue speck in the universe, it’s a miracle that life exists at all and that we have a piece of time that is ours, whether longer or shorter, to really be a part of the action.” John was most definitely part of the action.

In celebrating his life, and in consideration of what we have learned from him and what we loved about him the most, we remember John’s legacy to his family, his students, their students, and generations to come. Personally, I will remember his gentleness, his generosity, his kindness, his patience, and his tolerance. Having known John for nearly fifty years, I cannot separate the man from his devotion to his family, his craft, and his students.

For many of us, our first language is clay, with English a somewhat poor second. Ceramic materials are our grammar; their behavior is our vocabulary, they form our sentence structure. Tactility activates our message, generating layers of past and future tense, as texture and detail punctuate and activate physical response. The plasticity of the material and the severe criticism of the fire demand constant editing and revision. This is how many of us speak, and John, a master of this language, helped us refine and polish our speech, clarify our message, speak distinctively to our audiences.

I, and so very many of his students and colleagues in the field, are fully aware of the debt we owe him and the gratitude we feel for having known him. We acknowledge how he helped us learn the language of clay and fire and structure our artistic practice and how he supported us with fierce loyalty as our careers progressed. John, along with his wife, Susanne, built a wide and warm community that expands beyond here, beyond them, beyond us. It’s the main reason we came to the University of Michigan to study ceramics, and why so many of us stayed here to participate in and contribute to that community.

John loved his garden, and he nourished his community like a garden, bringing out the best in people around him. His efforts extended to many corners of the world; everywhere he went he cultivated an appreciation of all kinds of ceramics, from the work of folk potters to sophisticated contemporary ceramic sculpture and installations. He did this in big ways: through international research, exhibitions, and conferences, and nationally as well. But he also nourished and cultivated smaller, though not at all insignificant, local initiatives. During the 1970s, for example, John and Susie’s students and colleagues were strongly encouraged to play – one might even say dragooned into playing – volleyball on Sunday afternoons. The collegiality and friendships that developed at those volleyball games at their house created a network of lasting support and connection that meant showing up for and celebrating the important, thrilling, and even sometimes difficult moments in our professional and personal lives. It looked like volleyball, but it was a whole lot more.

In the early 1980s, John was one of the instigators of Clay/10. As I heard it from a couple of trusted sources, the idea arose in a van on the way back to Ann Arbor from Syracuse. Its occupants were lamenting the scarcity of exhibition opportunities for ceramic artists and the limited imagination of the gallery system in general. From that conversation, a plan emerged to form a cooperative, and seek out potential exhibition spaces, creating new opportunities to show work together. I was part of the group who did so steadily for a full decade, then intermittently, for another five years. That ten interpersonally-challenged hyperindividualists organized themselves and cooperated on a complex set of tasks, planning, publicizing, mounting, and documenting a series of successful exhibitions, as well as individually producing the work for them, was to a great degree because of John’s persistence, patience, and insistence upon civility.

While I will remember so much about John with pleasure, gratitude, and sometimes, outright laughter, I will also remember his tremendous grace in more challenging moments. As one of many witnesses to his character and his impact upon our world, I am aware of his influence as a testimony to his time on earth. Quietly and persistently, John cultivated the people and the world around him. And he is still at it, he is still part of the action.

Marie Woo

Few American potters traveled to Japan in the early 1960s. I can think only of Dan Rhodes, Donna Nicholas, and John and Susanne Stephenson who worked in Shigaraki; I worked at the Kaneshigi kiln in Bizen. It was relatively easy for foreign potters to become acquainted with Japanese potters: Tomimoto, Hamada, Kaneshigi, Tamura, and others were generous with their time and knowledge. It was an awesome experience to explore and discover the East, and Eastern ceramics. We were immersed in a totally foreign and seductive culture; it was all there for us to absorb.

Some of us also traveled to Korea in the 1960s. In 2006, I went there again to attend the International Academy of Ceramics (IAC) conference in Seoul, as did John Stephenson. There was a post-conference trip to a Buddhist temple where we experienced “a day in the life of a monk.” Wearing monks’ robes, we ate vegetarian meals, meditated in the temple, slept on a hard wooden floor, and were waken by a gonging bell before dawn. It required dedication, and John patiently appreciated the whole experience.

In the 1990s the Asian Cultural Council (an affiliate of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund) awarded me and John grants to research and document minyao or folk pottery in China, which was becoming extinct because of that country’s modernization policy. In the West, little is known about Chinese minyao, which is unlike the sophisticated imperial court porcelains featured in museum collections and published in books. This became a ten-year challenging adventure, as we traveled to remote parts of the vast land of China in search of pottery villages and dragon kilns. Because there was little demand for the traditional peasant ware, many kilns were cold. Potters had abandoned their villages and migrated to the cities in search of other livelihoods. In addition to visiting most of the Han potteries, we investigated the ethnic minority villages in the southwest that continue to produce simple, mostly hand-built, unglazed, and pit-fired pottery. In Tibet, the potters still make unglazed utilitarian ware and pottery with black, burnished surfaces, fired at ground level using wood and dung.

In our travels, we learned about many aspects of China’s deep and compelling culture: Chinese ceramics and their history; water-reduction firing for bricks and roof tiles; dragon kilns; Chinese opera; and Chinese food. Besides visiting pottery villages, we also gathered knowledge at villages that made handmade paper, brushes, umbrellas, masks, dyed fabric, and other crafts. As China modernizes, it is sad to see the demise of these rich traditional arts, and the essence of Chinese expression that began centuries ago.

In 2013, the exhibition Chinese Folk Pottery: The Art of the Everyday was presented at the University of Michigan Museum of Art. It included a symposium, which featured films and speakers from China. The exhibition has since developed a life of its own as a popular national traveling exhibition that is booked until 2019. John’s keen insight and dedication were indispensable contributions to the Chinese minyao project. It was my pleasure to have traveled many miles with John.

Ode to John

By Debbie Thompson

Reflective and patient

John would be

To look closely, and think visually

was key.

Proud of his family

proud of Susanne

John knew what mattered

and made it his plan.

Color, shapes

form,

and space

He knew how to use them

and put them in place.

I never saw him angry

or use harsh words

John chose working with mud and

feeding the birds.

Many an artist

he launched over time

His spirit is with us

and forever will shine.