What Good Are the Arts?

The world is facing a crisis. I don’t know what the situation will be when this gets published, but somehow the issues I raise might get lost in the shuffle. There is a reason bottom-line thinking is so highly regarded: it solves problems. And right now we are facing a problem whose sudden urgency cannot be ignored. Right now it matters what the right things are to do. Right now the ideal of keeping everyone safe takes precedence over so much of what we ordinarily take for granted and assume as part of our daily lives. It is that important.

However, the temptation might be to think because this problem-solving attitude is necessary in these circumstances, that the idea of balancing everything on some ledger of utility therefore takes precedence automatically. Yes, we are fighting for our lives. We must. But the lives we are fighting for mean something beyond mere survival. And we do what we must now so that in due course our future will have the chance to aspire to its greater humanity. As John Adams wrote in the midst of the American War of Independence,

“The science of government, it is my duty to study, more than all other sciences; the arts of legislation and administration and negotiation ought to take the place of, indeed exclude, in a manner, all other arts. I must study politics and war, that our sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. Our sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history and naval architecture, navigation, commerce, and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain.” -John Adams, in a letter to Abigail Adams (May 12, 1780)

If there comes an even greater temptation to downsize art, it cannot be allowed as an attack on art, but only as the condition of our extremity. We must not forget that the arts are on a bottom line as well, that “painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain” are all part of what makes human life much greater than mere survival.

Everyone reading this almost certainly gets why ceramics and pottery are worth doing. The truth is that it’s obvious to us. It is implicit in how we lead our lives. Art simply matters. We don’t need excuses and we are not convinced from any prior "justification." That is, we don’t check ourselves to see whether we are justified. It’s who we are. There may be some fence-sitters, and there definitely are those who don’t get it, but to us there is no doubt.

Where does this conviction come from? On what grounds does it rest? And how can something so familiar to us be so foreign to others? Those of us making a living from our practice continually confront this divergence. We have something whose value gets introduced to a world that may not be inclined, or particularly ready, to understand. How is it that we are so different from the doubters?

These sorts of question have a larger context as well. The arts in general have a public-relations problem. There are people, some very influential, who think art is a luxury. They disbelieve art’s value. To counter this, advocates within the arts sector attempt to establish why the arts matter. The skepticism of outsiders has consequences. But is making a case that art has inherent value convincing? If it isn’t obvious to "outsiders" can it even be shown? Don’t we need more objective confirmation?

I’d like to suggest that potters in particular can be a bridge. Potters understand the value of pots as often including the objective idea of function. Sometimes we might say that a good cup is one that holds liquid. Why this is important is that folks outside the world of makers, people who may not understand anything aesthetic about a pot, at least can tell if a cup works. And yet not all its value is circumscribed by mere function. A cup that holds liquid is a cup, not necessarily a good cup.

This is a relevant insight because the people in doubt about the arts are often stuck with the idea that the value that matters is what things are good for. You get arguments that the arts are good for the economy, good for cognitive development, for community building, etc. For these skeptical people, this is where the idea of value reaches its limit. Potters are poised to make a difference in this conversation. They both understand the importance of function but also that merely this is inadequate to the value in question.

As important as function is to functional potters, it does not explain why we make pots. No beginner picks up a lump of clay with the idea that "success" is merely a matter of function. Working professionals have even more at stake. We insist that our own version of function is worth supporting. That is, what matters is not merely function, but the specific way a vessel carries function among its attributes. Function is embedded in the larger whole of what we do.

Art enters the world straining to make new things known, to give birth to a cosmos of implication. Art searches out connections barely perceived. It is a celebration of meaning. It doesn’t limit itself to being merely instrumental in one way or another. That’s too small. That isn’t what makes art art.

There is a reason we have the idiom that a picture is worth a thousand words. Sometimes the medium is the message. Art can be a language unbounded by the more rigid constraints of our linguistic expectations. The physical, visual, and conceptual "grammar," "syntax," and even "words" of art practice get invented wherever imagination takes them. It’s why we distinguish creative exceptions within spoken or written language itself. It’s why poetry and metaphor are so potent. They resist reduction to things not themselves.

This is the problem with an instrumental idea of value: Few things are done just on that basis and even fewer are explained by it. Moreover, pretending art is simply an instrument for achieving goals puts it in competition with other useful tools. This can actually undermine confidence in our chosen means. Ends are often supported in multiple ways. What we value for non-utilitarian reasons may be the least well-suited to realizing those extrinsic utilitarian effects. What then?

Potters live with this reality. Mere instruments can break down or be superseded. However, when a mug gets chipped, develops a crack, or becomes unusable for drinking, how often does it turn into a pencil holder? That is, somehow it must be worth something in itself, even damaged, to be held in such high regard. To recognize art as inherently valuable you need to see beyond how it performs some adventitious service. A broken pot may still retain its own value.

Some things are simply precious in their own right. Which is not to say we always have the right words to explain their value. Our appreciation of art is not always so much explicitly in the foreground as it’s the accepted background of what we do. It is not normally questioned because for us it’s not something in question. This is more a matter of human practice than a confrontation with something ineffable.

Asking for art to be justified is an extraordinary request. No child ever picked up a paintbrush to benefit the economy. The reason of art, if there’s such a thing, is not its instrumentality. But somehow in advocating for art we don’t feel confident making that claim.

The facile utilitarian notion has undermined our belief in not only what we do, what motivates us, but also in whether we ourselves have value as artists. Thankfully most studio potters are immune to this. We know better. We may prefer calling ourselves “craftspeople," but that’s both a sign of how far the stigma against art has reached and a defiant declaration that we know we matter.

The things that "justify" the arts are never sufficient to motivate us to engage with or participate in the arts. That’s because the arts are merely a means as an instrument. We are motivated by our ends, not our means. The justification is not the motivation. As good as the arts are

for the economy, and they are, you cannot tell an artist they are doing (or should be doing) what they do just to serve the economy. That is nonsense.

When the value of art becomes so intertwined with what it’s good for, not what it is in itself, we often don’t know how to respond. We find ourselves standing at the same time both inside the arts and outside them. This double vision can be disorienting. It’s paradoxical if not conceptually schizophrenic. We are caught feeling the need to be justified at the same time as we are committed to the arts being something worth justifying.

There is an important difference between motivation and justification. Motivation doesn’t always rest on uncertainty. Justification does. It’s always conditional. Some things are obvious to us while others aren’t. Justification is necessary when we have doubts or need assurances. But, we are not completely surrounded by doubt. Questions get framed by what stays fixed. Doubt makes itself known when things don’t add up. This is the exception. We can say so because there IS such a thing as adding up. We never doubt everything all at once. Some things have to hold fast. There are legitimate questions. Others are not.

One way to look at it is that questions operate as measures. They set out the terms of our understanding. And to do that they are not themselves ordinarily under question. Proper measures have a role where doubt isn’t a function. They may have already passed the test of bygone insecurity or now simply be accepted for what they are. What they do isn’t up for debate. As measures, they are methods of representation. They are the things doing the measuring, not what gets measured.

There is a profound and fundamental difference between a measure and what gets measured; between the things we take for granted and the things that need to be accounted for. The double-vision inducing quandary suggests we aren’t always impressed with what does the measuring. Somehow we need to get clear on the source of our disorientation. We need to focus on the whole picture. That means taking a closer look at things hidden right before our eyes.

Measures are typically far removed from the foreground. We use them, but they are not seen. Measures are not what we attend to. They have been relegated to the background only because we rely on them so heavily. They don’t always need to be tested or otherwise examined. Measures are what make sense of things. In the foreground we’re naturally interested in the things that get measured. Why else measure?

There is no comparable question for the measures themselves. They simply are. Our confidence is our confidence in measuring. That assurance is the bedrock of how we live as humans. Somehow we have traded a certainty that art belongs in our lives for a conditional assessment that art matters for non-art reasons. But what if the arts themselves were a measure?

It isn’t always easy to see where we’ve gone wrong in mistaking a measure for something merely measurable. We don’t always see the consequences of getting it confused. We don’t see why our perplexing double vision threatens our form of life, but our lack of clarity does make a difference, and it’s important to see why.

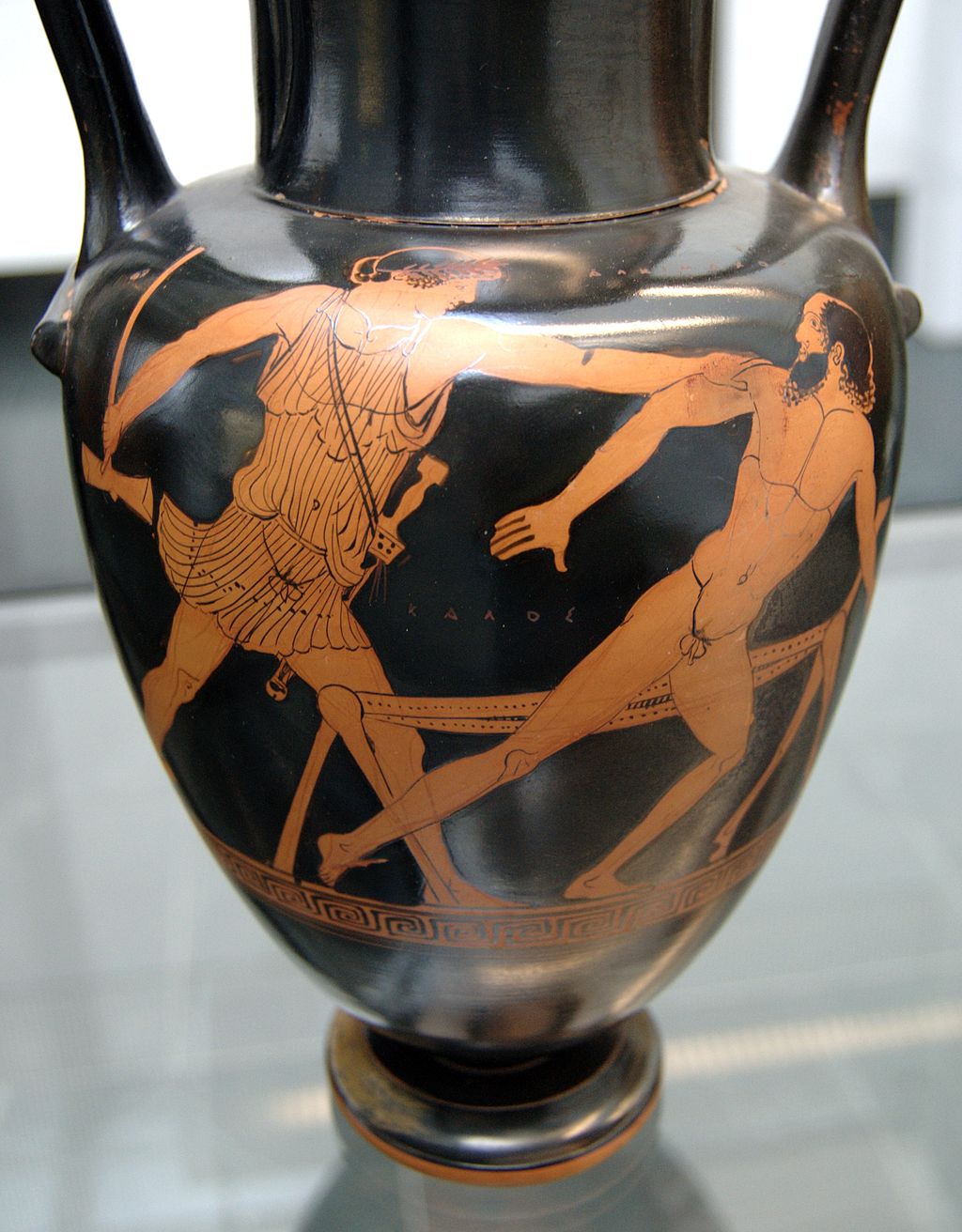

The point is that art functions in human lives in a way not captured merely by being measured, by being put to the test, by being subjected to doubt, by being laid out in a Procrustean bed. There’s a fundamental difference between the inside view of the arts and an outsider’s. From the inside we see measures as measures. We use them that way. From the outside we don’t use these specific things as measures. This role is simply alien to our way of life. The best way to understand them is if we measure them. We don’t accept them until they can be justified. At least, that was what Procrustes was thinking.

Part of the confusion is that some art seems so obviously objectionable. No one can like all of art. Liking something may even mean you are excluded from liking something else. But disliking or failing to appreciate one or more examples of art is not an indictment against the arts as a whole. And neither, it must be said, is a particular instrumental benefit proof of art’s general value. If the question is about the value of art as such, that art itself matters, there must be another argument. Here it is:

Some art is indispensably a part of each person’s being. There is no human form of life that doesn’t include art in it. We listen to music. We sing in the shower. We doodle. As kids we once played with dolls and toy soldiers, an elaborate theater of wonder and imagination. We make up stories, myths, poetry, and are absorbed by them. Art can be as ephemeral as a gesture, as concrete as a monolith. Human life dances through it all.

You cannot be human and fail to have these sorts of experiences. The truth is that we wouldn’t know what it was like to be human in the absence of art. Human history, from its earliest evidence, is that of creative beings. Prehistoric folks didn’t need to be justified by the economy or anything else to paint caves in Lascaux. Humans simply care about things like beauty, about exploring the unknown, about mystery, and telling stories. These are our credentials. We remake the world as something better than it was. You cannot package that in merely instrumental terms.

The defamation of art is a chosen posture in the political and funding games. An amnesia about art’s role seems expedient to big fish playing for bigger payoffs. Unfortunately the same seems true for the smaller fish milling around looking for scraps. Despite the inducement of starving wages, artists don’t seem to be on the winning side. Proving art’s worth is a misdirection while the "referees" replace what actually mattered.

However, art isn’t waiting to be justified. It is instead a thing we use to make sense of the world, and art needs our help. Art and creativity bring the world and our imagination into focus. It’s how we navigate the world, how we come to know ourselves. Along with language, culture, and community life, art stands at the foundation of what it means to be human. Doubting the arts’ value is a hallucination of the skeptic’s uncertainty. It’s a delusion of poor, befuddled advocates trying to stand both inside the arts and outside them. Art’s value is inseparable from our own humanity.

Whether this moves the needle on policy and funding debates is up for grabs. Some folks are in too deep, but the rest of us have to fight the notion that the arts have zero non-instrumental value worth talking about. When someone asks for art’s justification they are looking for permission. They are telling the fable that art needs to first pass muster. If it isn’t good for anything, the reasoning goes, it can’t be any good. If it isn’t good, it isn’t worth doing. As if art needed an excuse.

Justifying the arts has actually threatened to push the arts out the door as something conditional on someone’s approval. It has forced a wedge between art and our motivation to be with art, to make our home and our lives in the presence of art.

Ordinary studio artists will find this relevant: Part of our everyday experience in the studio is that we make what we make and don’t need to be convinced it’s worth doing. At the very least we have tentative confidence we are aiming at the right things. Some folks understand. Others don’t always get it. Not every customer who walks past our sales booth is seeing what we are seeing. There is a disconnect. And we often like to know why that is. If what makes a pot good is obvious to us, or why a sculpture hits the mark, why doesn’t it have the same purchase on other people?

So artists must be educators in addition to being makers. Unless we are being obvious and wholly scrutable, we are occasionally confused with merely making sounds. Differentiating signal from noise is what stands between those who can make sense and those who can’t. To see something in its own terms is a matter of learning to use it itself as a way of measuring. It’s coming to see that in these terms THIS is what a good pot means. This is what’s being aimed at and this is the idea being conveyed. If the artist cared enough to create in these specific

terms, these terms are the measure of what counts. Marcel Duchamp notwithstanding.

I will end on the note that potters are in a great position to see through the haze of deception. Despite being downgraded and disparaged in elitist wings, we know better. What we make as studio potters already has a home in people’s lives. You can’t be human and not drink, so why not drink beautifully? You can’t be human and not eat, so why not eat things conveyed to us with grace? The ceramics community is not deceived.

Art often is the difference between making the world more livable and settling for uninteresting and unimaginative. Even the most humble homes are decorated in some manner. It’s our human nature. Potters, hand-builders, and ceramists of all stripes are there to create vases for your flowers, bowls for your soup, and sculptural forms for your aesthetic pleasure. Clay-oriented artists understand more about human nature than technocrats ever will.

My hope is that folks in the ceramics community will continue to engage in the broader discussion of why art matters, especially in this period of uncertainty. As many of you move toward online learning and exploration, let that be a beacon to guide you. The people currently in charge need all the help they can get……..

Endnotes

All images, unless otherwise noted, were sourced and available under public domain.

LASCAUX 4, Montignac, Dordogne, France. Pictures takes in the part called atelier.

THESEUS AND PROCRUSTES. Side A from an Attic red-figure neck-amphora, 470–460 BC. From Nola.