To My Role Mother from Her Student

"A remembrance of Harriet Brisson" by Jay Lacouture, originally delivered as a eulogy at Rehoboth Congregational Church, September 19, 2019, and edited for publication in Studio Potter.

Nineteen-seventy-six was an auspicious year. It was the year of our country’s Bicentennial, and the year I went back to school to study ceramics at Rhode Island College (RIC) after a six-and-a-half-year hiatus. During that time, I had gotten married, had two children, and developed a keen interest in clay.

Many celebrities have been known by only one name: Elvis, Madonna, Michael, Prince, and so on. During my first semester at RIC, I heard of this phantom figure in the art department known by the singular moniker, Harriet, who was on sabbatical and in Japan at the time. I saw her sabbatical exhibition in the Adams Library Gallery. Along with some complicated geometric forms, there was a modest arrangement of pots on a tatami, set for a Japanese tea ceremony. This was my first encounter with chanoyu (the way of tea). Little did I know that this sociocultural experience would permeate my teaching for nearly forty years. In essence, Harriet became my teacher before I even met her.

Since her passing, I have continually pondered, “What would my life be like if I had not met Harriet Brisson.” What follows are some of the personal memories that come flooding back when I think about my Role Mother.

In the summer of 1976, she returned to RIC as the department chair, I became her work-study student and remained so for two years while I finished my bachelor’s degree. When she showed up in the studio, she put on her infamous bib coveralls and got to work. After class, like Superwoman, she stepped into her tiny office, removed her coveralls and, impeccably dressed, was ready for the next faculty meeting or other professional duties. From that summer until August 24, 2019, we remained dear friends in all things clay and all things of the heart.

At RIC, I met this guy from New Hampshire, a potter who had founded a wonderful publication, Studio Potter magazine. Gerry Williams was a close friend of Harriet’s and became a valued friend of mine. The summer of 1977, he was offering a wood kiln–building workshop at his studio. I was eager to learn about wood firing, but as a full-time work-study student and father of two kids, I couldn’t afford to take time off from my job to attend. Using her discretion as my work-study supervisor, Harriet told me, “Go to the workshop. We will continue to pay you, and when you come back, we’ll build a wood kiln in the kiln yard.” I think she also may have paid for my workshop registration. Through that early exposure, Harriet lit a fire in me as a young potter that continues to burn.

During the 1990s, Harriet and I served on the board of trustees for the Studio Potter organization, the nonprofit entity that helped Gerry sustain the magazine. Harriet served for nearly twenty years, nine of them as chair.

One Saturday evening in 1979 when I was in graduate school at West Virginia University in Morgantown, the phone—one of those big yellow plastic wall phones that never broke—rang. A familiar voice said, “Jay, it’s Harriet. What are you doing tonight? Dave and I are in Western Pennsylvania, only about two hours from you. I just picked up a parabolic reflector to build another solar kiln. Would you like visitors tonight?” Of course, I was elated. By this time Harriet and Dave, her husband, and soul mate since her undergraduate years at RISD, were part of our family. When we got together, it wouldn’t be long before Dave was playing with the kids on the floor in their room. As Harriet once remarked, “Dave is more interested in having meaningful talk with kids than dribble conversation with adults.”

I can still picture the two of them driving some 600 miles, heading east down I-78 with a huge, eight-foot parabolic reflector hanging over the sides and back of her little white Datsun pickup, all in the service of her adventures in alternative energy for the potter. Alternative energy? What a novel idea! A bit ahead of the curve in 1979, I’d say.

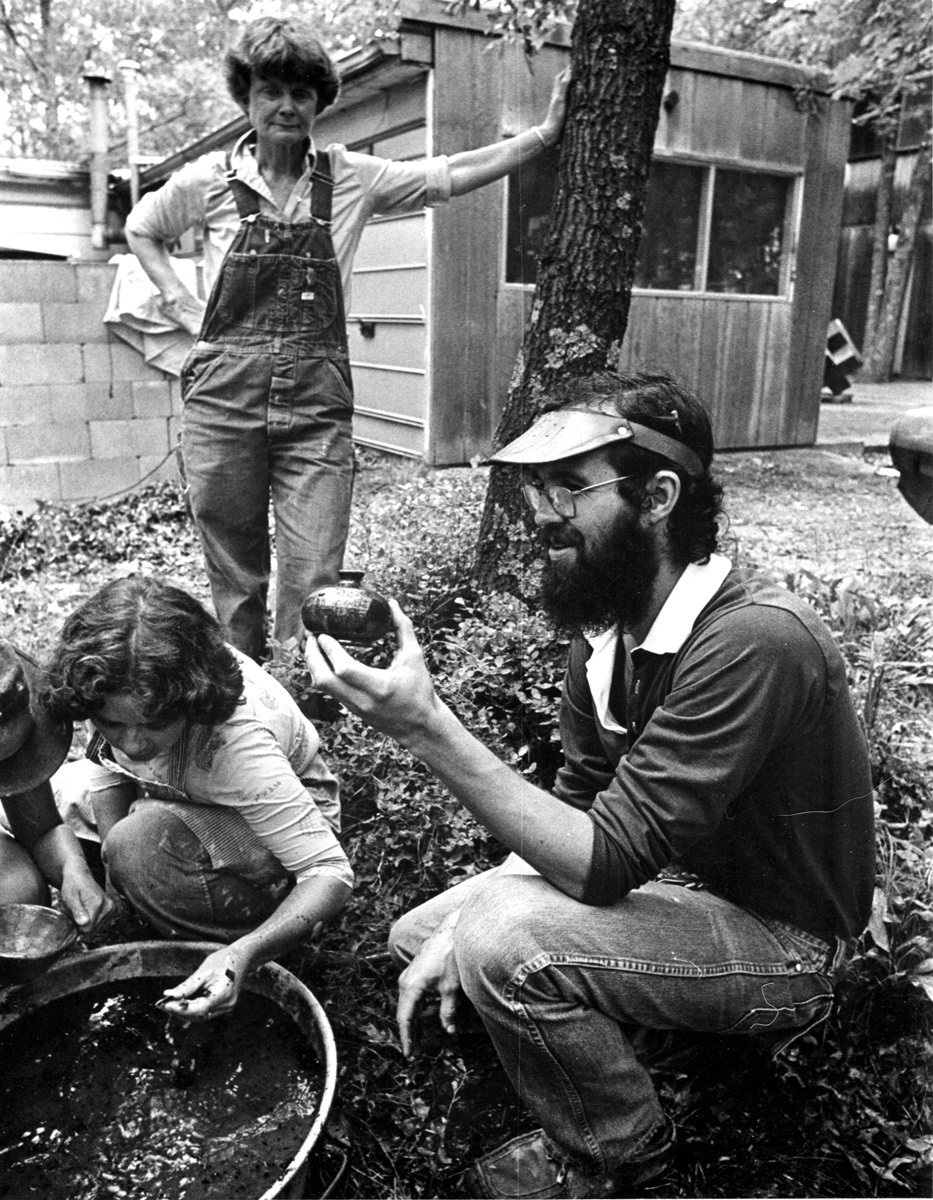

When I returned to Rhode Island in the spring of 1980, with just about enough money to coast our U-Haul truck into my parents’ driveway, Harriet asked me to help her lead a one-week raku workshop at the Newport Art Museum, to be held that August. She would fire her charcoal-fueled raku kiln, and I would fire my coke-fueled kiln, and we would compare results with the participants. It was so Harriet to extend our technical information base through comparing results, charting our information, and seeing who had the most complete reduction. She also gave me half her honorarium.

One of the people in the workshop, a high school clay teacher named Rosemary Day, mentioned that she thought Salve Regina College was looking to hire a ceramics teacher. The last day of the workshop, I walked down Bellevue Avenue, portfolio under my arm, through the gates of Ochre Court at Salve, and got hired virtually on the spot. Thus I began a thirty-eight-year career teaching ceramics. I heard someone say once that “coincidence is God’s way of being anonymous.” In this case I think that my guardian angels, Harriet and Rosemary, were certainly there to grease the skids for me.

In 1983, Harriet organized a panel for the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts (NCECA), on alternative energy. She asked me to participate. I became involved in NCECA as a voulenteer, board member and served as president from 1991 to 1992. I would never have had the guts to consider doing this without Harriet’s support and guidance. Heck, if she thought I could do it, then I could.

During my presidency, NCECA celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary, and Harriet thought NCECA should have some kind of silver anniversary document, highlighting the organization’s history and achievements. As she was about to go on sabbatical, she offered to research and write it during her leave. She had lived that history, having become a member in 1968, but to ensure that her account was accurate, she spent countless hours driving back and forth to Alfred University delving into NCECA’s archival materials related to the organization’s history. There was no personal gain for her from the project; Harriet just took one for the team. I often think she did it to help me look good as president. Well, she sure did. This manuscript continues to be relevant and regularly referenced by the NCECA leadership.

My dearly departed friend Karon Doherty, a former ceramics colleague at UMass–Dartmouth, once lamented that she had never had a woman ceramics professor. With all due respect to Harriet, it never occurred to me what gender Harriet was or was not. She came of age in her career not as the result of some Title IX legislation, but because she competed with other artists and succeeded. She did it all, from exhibiting her work internationally to shingling the roof of the kiln shed on campus. In the larger ceramics community, some affectionately referred to her as the Katharine Hepburn of ceramics.

In 1998, when I built my two-chamber wood kiln at the Carolina Pottery, in Rhode Island, Harriet was there to schlep bricks, mix mortar, and do whatever else was needed. My young students were in awe of this “older woman” who worked as hard as they did. I couldn’t wait to fire it so that they could really see the “old lady” in action. She stopped firing around 2010. Her spirit still looms large with the firing crews. We often ask each other during a firing, “What would Harriet do?”

I once heard a colleague say, “All a student needs is one teacher to model their life after. The problem is, a teacher needs a good student every semester.” There is probably some sort of mathematical relationship here into which Harriet might have some insight. What I do know is that I was fortunate to find my Role Mother at RIC in Harriet Brisson. She critiqued me, built and fired kilns with me, served the greater ceramics community with me, laughed with me, and cried with me as we navigated life together as dear friends for more than forty years. What a gift.

I believe Harriet was happiest when she was walking in the woods behind her home and studio in Rehoboth, Massachusetts, along the Palmer River, or along her beloved beach at Green Hill, Rhode Island.

In closing, I offer a fitting poem by Maya Angelou:

When Great Trees Fall

When great trees fall, rocks on distant hills shudder, lions hunker down in tall grasses, and even elephants lumber after safety.

When great trees fall in forests, small things recoil into silence, their senses eroded beyond fear.

When great souls die, the air around us becomes light, rare, sterile. We breath, briefly. Our eyes, briefly see with a hurtful clarity. Our memory, suddenly sharpened, examines, gnaws on kind words unsaid, promised walks never taken.

Great souls die and our reality bound to them, takes leave of us. Our souls, dependent upon their nurture now shrink, wizened. Our minds, formed and informed by their radiance, fall away. We are not so much maddened as reduced to the unutterable ignorance of dark, cold caves.

And when great souls die, after

a period peace blooms, slowly and always irregularly. Spaces fill with a kind of soothing electric vibration. Our senses, restored, never to be the same, whisper to us. They existed. They existed. We can be. Be and be better. For they existed.

See you on the other side of Cone 12, Sensei.