An Interview with Ben Cohen of Ben & Jerry's Ice Cream

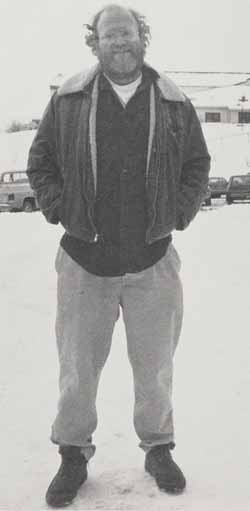

Ben Cohen stands firmly grounded in front of his new ice cream factory in Waterbury, Vermont, contemplating with satisfaction the successful conclusion of a two-year negotiation that resulted in the opening in the Soviet Union of a new ice cream emporium to be called Ben & Jerry's Vermont "Iceverks" Ice Cream. This Soviet Union coup is only one of many on the long road he has traveled since Ben & jerry's first opened in Vermont.

Ben & jerry's, Vermont's Finest All Natural Ice Cream, was founded in 1978 in a renovated gas station in Burlington, Vermont, by childhood friends Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield. With the help of an old-fashioned rock-salt ice cream maker and a five-dollar correspondence course in ice cream making, they soon became known for their funky flavors and a year later were delivering Ben & Jerry's ice cream to grocery stores and restaurants. Now Ben & Jerry's factory in Waterbury is the second most popular tourist facility in Vermont, after the Shelburne Museum, and hosts more than 23,000 visitors a month during the summer. In 1989 their sales reached $57 million.

The legend of Ben & Jerry's is known far and wide, but connected with it is a rumor that Ben Cohen, founder and company boss, was once a potter. To discover if there is any basis of truth to the rumor Studio Potter sent its correspondent at considerable expense—he came back with nine quarts of ice cream—to Vermont to interview Ben Cohen.

The corporate CEO was discovered hard at work in an unusually informal habitat, an office housed in a modest wooden dwelling immediately below his spiffy new ice cream factory. He was dressed in rumpled flannels, glasses, and beard and seemed in an expansive mood due, perhaps, to leaving within the hour for vacation. The interviewer began in characteristically trenchant manner: Now, Mr. Cohen, about this rumor . . . ?

True. My first experience with clay was in kindergarten making dive bombers out of little, round cigar-like pieces of clay with toothpicks stuck in them. I space also remember making a little sculpture with a head and big, wide, open mouth, used, of course, as an ashtray.

Once, when in elementary school, I saw a film that made a big impression on me. In it a boy bought a vase for his mother's birthday but while walking home he dropped and broke it. A girl appeared and led him through the woods to the shop of a potter who made him another vase. I loved it. The film is etched on my mind and may have been responsible for my later claywork.

I always was interested as a child in manual things and working with my hands. I remember playing with hammers and saws and declaring that I wanted to be a carpenter when I grew up, though my parents responded with, "Oh, no, honey, you want to be an architect." My father was an accountant and eventually became the manager of a direct mail business. My mother had gone to Pratt Institute and was always drawing and painting.

I went to Colgate College because my parents wanted me to go—besides the draft was on—but dropped out after a year and went to California and bummed around. Later I discovered that Colgate had an exchange program with Skidmore College (I had heard Skidmore had a good crafts department) and ended up going there and taking jewelry, pottery, threedimensional design, and film.

Actually, I failed the threedimensional design class taught by John Cunningham. Funny thing, the other day some of his Skidmore students came by here as part of a joint project with a business class. The business class had been studying Ben & Jerry's and commissioned the art students to make a statue of me. So they showed up at Crunchland, the home of our new business where we make Rain Forest Crunch, with a big U-Haul and a life-sized statue of me. I was shocked and aghast. Ha, ha.

Ben & Jerry's is named "National Ice Cream Retailer of the Year" in 1984 by the National Ice Cream Retailers Association and Dairy Record magazine.

At Skidmore I studied pottery with Regis Brodie. It was the first time in my life I was seriously motivated by anything. I started working with slabs, then made a lot of coiled sculptural pieces about three feet high. Regis is a great teacher and I learned a lot. He would talk about "the beautiful pot"— the one that seemingly lifts itself off the table—and frequently proclaimed that "the joy is in the journey." We built a woodburning kiln that never got up to temperature and did some raku stuff that was nice. Toshiko Takaezu came up once and put on a demonstration. It was a wonderful year.

I made functional pots on the wheel: plates, low bowls, canisters, teapots, water pipes. I enjoyed wheelwork. Mostly I made stoneware and nevergot into porcelain, but glazing was my big problem. I spent all my time in the potshop and even stopped being enrolled at school just to hang out at the shop with my dog Malcolm.

After Skidmore I decided to move to New York City and become more exposed to influences as a potter. The reality of New York was, however, that you spent all your time making money to pay for the expense of living there. I did become a member of a small coop on Forsythe Street, in lower Manhattan, and even delivered wheels for the Baldwin Pottery. I worked to pay bills by clerking at Bellevue Hospital on the night shift of the pediatric emergency ward and drove a taxicab.

I was very anxious to get out of New York when I saw an ad in the New York Times for a crafts teacher at a school for troubled adolescents. It was on a 600-acre working farm in the Adirondacks at a place called Paradox, and I said, "Oh, boy, this is perfect for me." I managed to persuade them to hire me even though I lacked a bona fide college degree and moved to the school to help set up a crafts program.

There had once been a pottery at the school. I found an old wooden pottery wheel left rotting on top of a manure pile in the barn and rebuilt it and welded and cast several others. (I have to admit Ted Randall did a better job of his wheel.) We made clay in an old bathtub, just as Regis had taught us, mixing the powder around and then dumping in buckets of water. I built a rack for sliding shelves with hardware cloth on the bottom on which to dry the loose slurry. It worked pretty well.

I built a kiln out of insulating firebrick-with rods going through the flat top and compressing the bricksbased on plans Regis had mimeographed from somewhere. We built a shelter around it, hooked up two Big Bertha burners, bricked up the door, and sure enough the thing got hot. The kids loved it.

The pottery was a popular place. I tried to give the kids a successful learning experience since most of their experiences had been unsuccessful ones. By learning to throw pots they could reestablish their faith in the learning process as well as gain confidence in themselves.

Toward the end of my stay at the school, I worked half time for the school and half time for myself as a potter and began to earn a living by selling pots at craft fairs. I had a big white Ford van I drove around the country trying to sell my pots- Rochester, Long Island, wherever. At each fair I set up shelves and unwrapped pots one by one. Of course, I never sold any so I'd have to wrap them all up again. It was tough. Indeed, it was one of the most discouraging experiences of my life, and I felt the lowest I have ever felt.

Bryant Cumbel says about Ben & Jerry's on NBC's "Today" show, "This is serious ice cream!"

By this time, my friend Jerry and I decided we wanted to go into the food service, either by starting a bagel shop or a homemade ice cream place. Jerry and I had been longtime friends from Merrick, Long Island, where we met in a junior high gym class. We were the slowest and fattest kids in the class, and while the whole class ran around the track there would be Jerry and me huffing and puffing and pulling up the rear about half a lap behind. You make fast friends with whomever you can find back there.

To get experience in the food service I became a baker's helper. I loved the kneading and wedging, it was so much like clay. I kept telling the baker this but he didn't want to hear about it; that wasn't the way he saw it. One day I was fired because I made some dough that came out salty. In addition, he didn't like the way I cracked eggs. One of my jobs was to crack and separate eggs, dozens and dozens of them, into a stainless steel container. I was so intent on cracking and separating them that I didn't notice the white was oozing down the side onto the counter and had accumulated in a big puddle. Boy, did he get mad, and that was the end of my career as baker's helper.

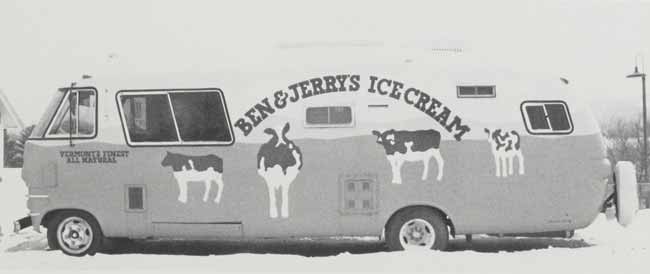

Ben & Jerry’s launches its "Cowmobile" in i 986, a modified mobile home used to distribute free scoops of Ben & jerry's ice cream in a unique, crosscountry marketing drive—driven and served by Ben and jerry themselves. The "Cowmobile" burns to the ground outside Cleveland four months later. Ben says it looks like "the world's largest baked Alaska."

In 1978 we opened an ice cream shop in Burlington, Vermont, with $4000 apiece, plus another $4000 on loan from the bank. We had discovered it would cost $40,000 to buy used restaurant equipment to start the bagel business, so we figured ice cream had to be cheaper. We discovered a five-dollar correspondence course

given by Penn State University on how to make ice cream, and split the course between us.

As a transition from being a potter to an ice cream man, I determined I would make all the bowls, plates, and mugs for the shop. I went back to the school in the Adirondacks to make them, and I glazed them with what I thought would be a foolproof color. But, since my trouble had always been glazes, the color fired out that ugly blue we all love to hate. As is often the case, however, it didn't look quite so ugly to others. We had the blue pottery bowls for eating in and paper containers for taking out. Jerry always switched to paper toward the end of the day because he didn't like to wash the dishes. One customer on Jerry's late shift always insisted on having his ice cream in a crockery bowl, and Jerry always got mad.

Ben & jerry's introduces its Cherry Garcia ice cream flavor, named for Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia at the suggestion of two "DeadHeads" from Portland, Maine.

The challenging part of Ben & Jerry's business has been figuring out how to integrate a concern for community with making a profit. We have a Mission Statement: first, we have a Product Mission to make the highest quality product possible; second, we have a Financial Mission to make a reasonable return for our shareholders; and third, we have a Social Mission to make a contribution to the community. Following that, we measure the success of our company by developing a twopart bottom line: our success is measured by how much money is left over at the end of the year, and how much of a contribution we made to our various communities. By our communities we mean our employees, the local community, the national community, and the global community.

In the beginning, our managers were confused over the perceived incompatibility between the profit and the social missions. We've been working on the problem and have learned now that the solution is integration by finding courses of action that make a contribution to both missions at the same time.

One example is our Peace Pop. We came up with a chocolate-covered ice cream pop on a stick that we sell at a profit. This product has to have a wrapper so we decided to utilize the space on the package to promote political action that in our opinion will improve the quality of life for people in our country and all over the world. On the inner wrapper we print a message that says the United States is spending 40 percent of its budget on the military and that equals 300 billion dollars. We show that 1 percent of that equals 3 billion, and that if you ate one ice cream cone a minute, it would take you thousands of years to eat 3 billion. We use the packaging to support an organization called 1% for Peace, a separate organization I helped to found, that seeks to redirect 1 percent of the U.S. military budget to peace through peaceful activities. The packaging didn't cost us anything more; we already had to have it. Normally we would be explaining how great our ice cream is, but instead we devote the space to a social mission.

Another example is our Rain Forest Crunch, a cashew and Brazil nut butter crunch that is made by an independent company I formed specifically for the purpose. The company purchases Brazil nuts through a nonprofit organization called Cultural Survival that supports people who live in the rain forest, thereby demonstrating the rain forest can be more profitable as a living forest than as land turned into plantations by cutting down the trees. Money from the sale of the nuts goes back to form a cooperative Brazil nut processing facility so that people who are currently paid 3 or 4 cents per pound to harvest nuts will start receiving 50 cents instead. Ben and Jerry's buys the Brazil nut cashew butter crunch to use as a flavor in its ice cream and at the same time supports a company that is aiding survival in the rain forest. The company also donates 60 percent of the project to environmental and peace groups.

A third example is the ice cream flavor we call Chocolate Fudge Brownie. We buy the brownie from a bakery in the Bronx run by a Buddhist community that works to house the homeless and train them to become bakers. By selecting it as our supplier, 100 percent of the profits we pay them go back to the community. These are some of the ways we are able to integrate the missions of profit and social purpose.

Ben & Jerry's also donates 7.5 percent of its pre-tax earnings to the Ben & Jerry's Foundation, a nonprofit institution established in 1985 to award grants to locally based community groups dealing with human issues, with a focus on children and families, disadvantaged groups, and the environment.

Ben & jerry's sends its scoop vehicle to Wall Street to serve free scoops of That's Life and Economic Crunch ice cream following the October 19 stock market crash.

Most people describe business as an entity that produces a product or provides a service. The normal message is to come to work from 9 to 5 and earn your money, then when you go home you can do good for people in your spare time or with your spare change. But leave your values at the door because here we just want you to make money.

I see things differently. I define business as a combination of organized human energy and money, and that equals power. When you have 300 individuals organized into a business, it is an incredibly powerful tool. All we are saying is that we're going to run our business according to our personal values and use this tool to make money as well as to help people. We say that when you are at work, you are at your most powerful. When we organized our business, we actualized our values.

This approach is not particularly unique to Ben & Jerry's. A lot of small companies do business this way. One is Consumers United, a health insurance company located in Washington, DC, that has all its money invested with social screens (that is, socially and environmentally acceptable businesses). They have a very low salary ratio: the highest-paid employee cannot earn more than 31/2 times the lowest paid person. Ben and Jerry's has a 5-to-1 salary ratio. Normal businesses have a 15- to-1, and big corporations start getting into the 50-to-1 ratio and above.

Ben and Jerry are named U.S. Small Business Persons of the Year by President Reagan in a White House Rose Carden ceremony. Ben finds an Italian waiter's jacket to wear, while ¡erry sports his only suit; consequently they go unrecognized by the press.

When our business was very small and housed in the old gas station, I was truly responsible for everything. If things didn't work out, I had no one to blame but myself. Now the organization is so big I have to work through many people. As boss of this corporation I'm not nearly as free as I was when I was a potter. Currently, if I want an ice cream flavor changed, I have to go though a number of committees to do it. If a potter, on the other hand, wants to change a body, he changes it. If he wants the pot to go up in the air, it goes up. Thafs the wonderful part of a potter's life. Ifs so immediate. And ifs nice to be able to knock off when you feel like it. Potters are lucky to have a livelihood and lifestyle whereby they can express themselves and be their own boss. I miss that here.

Many potters, however, are in their own little worlds and isolated from the larger society. They could become more socially aware and take more stands. They could be helping to influence people who buy their work through, say, the tags on their pots. As consumers they could be more socially responsible in regard to their clays and chemicals. Switching health insurance to an organization such as Consumers United would make a lot of sense. They could also restructure their affairs so that they don't pay as much in taxes, since 40 percent of all taxes is used for what I consider horrible purposes. There are many opportunities open for ways to contribute to peace and to environmental well-being.

Ben & Jerry's rescues the legendary Newport Folk Festival from oblivion by becoming its sponsor, and the two-day outdoor concert is recorded for national broadcast on American Public Radio. Ben and Jerry receive a standing ovation when they address the concert from the stage.

Many of our ice cream flavors are named after suggestions from customers, though I doubt if there will ever be a Stoneware Crunch—we do all we can to keep stoneware out of the ice cream. My favorite Ben & Jerry's flavor is Cherry Garcia.

_ _ _ _ _

Pssst: the original recipe for Cherry Garcia is in this issue! Unfortunately, print versions are sold out, but the digital version of the original print issue is available to members (to log in click the yellow button at the top right of the page), and the PDF version is available for download here.