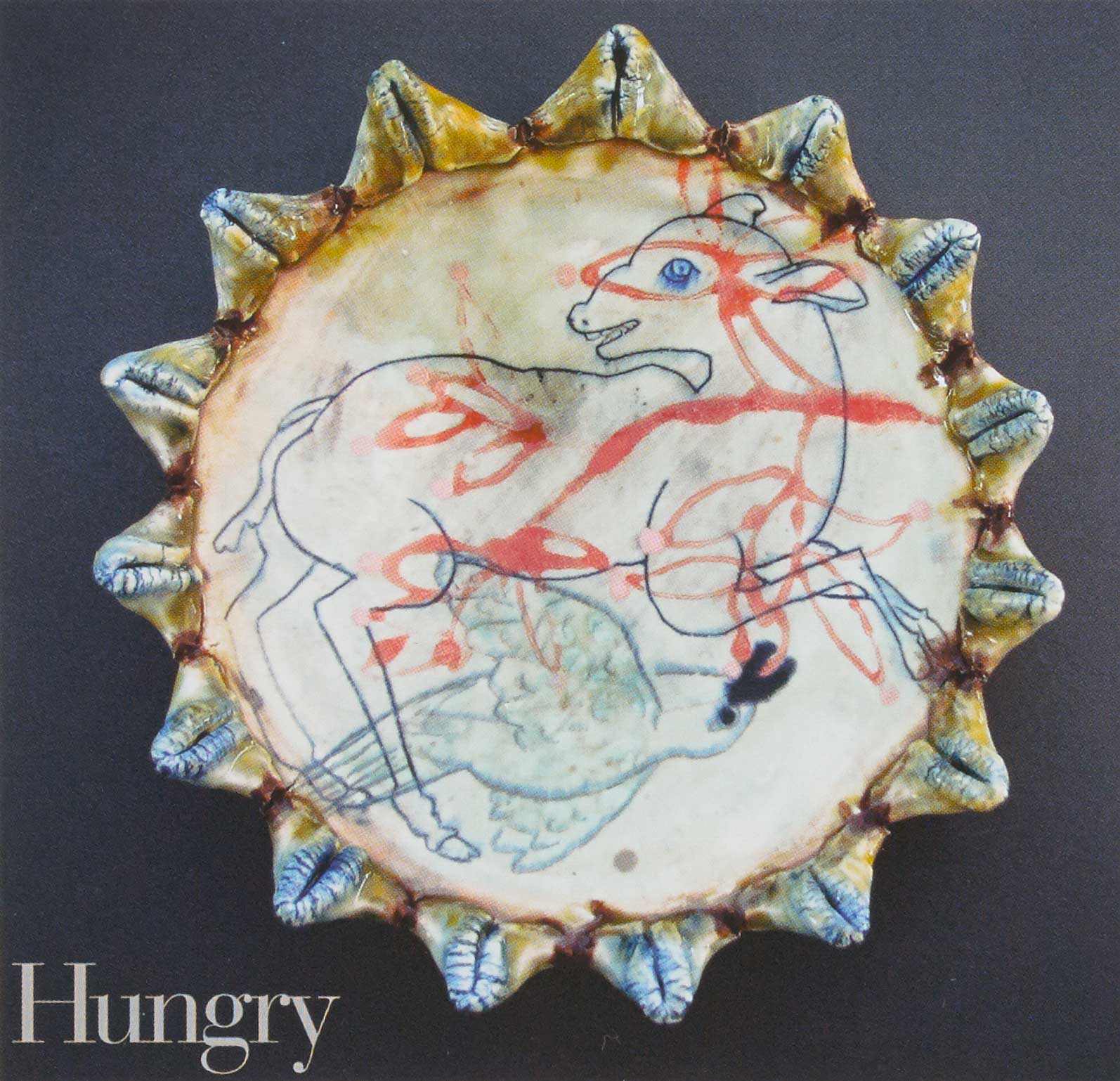

Hungry

There is great skill to accepting one's imperfections. Greater still is the ability to capitalize on them enough so they become an asset, or at least an honest definition of what one has to offer. Making pots has been a way for me to accept my humanity and understand my physical body. I learn both by investing in the process of making pots and by watching what the object becomes out in the world. After a lingering adolescence, I began to understand that my connection to making pots was directly connected to my relationship with food.

Scarry's book unravels the complexity of making our human pain sharable. She explains that by its very nature, bodily pain removes our ability to express that pain accurately through language. A scream or cry is the best way to communicate the pain we feel when we've stubbed a toe, as opposed to fumbling through the very lousy job language does by saying, "My foot hurts." An art object, like a scream, can communicate pain in ways that language cannot.

I have struggled with the pain of being overweight since the age of nine. I went on my first diet at eleven, truly hating my body. Since then, I have tried most of the major diets out there, only to end up disenchanted and hungry. I have watched my body react to every awkward thing that has happened to me by eating or not eating in order to find a new level of "comfort." I have loved eating and I have hated it, and I have been a slave to my body. It is this over-analyzed self-realization that I bring to making pots.

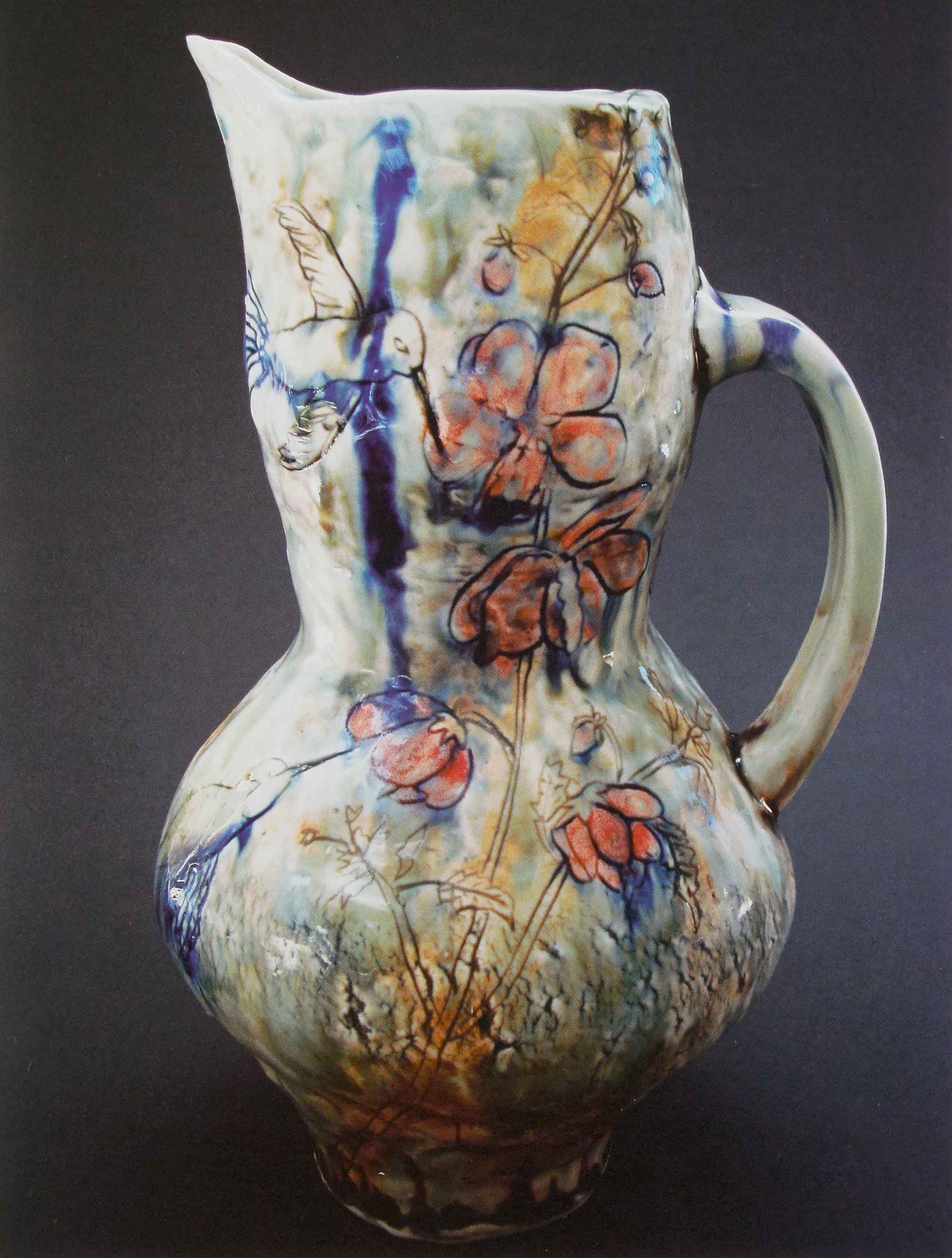

Since moving to Louisiana nine years ago, I have been exploring the body's complexity in my work. Southern Louisiana has a reputation for indulging in desire, and I admit I have enjoyed learning about that culture. My desire to eat, say, a whole pie comes from a longing deep within, on a fine line between pleasure and pain. Eating that pie pushes social boundaries, both in my physical appearance and in my un-ladylike behavior. Making dessert platforms and oversized serving vessels allows me to examine more deeply my ideas about physical fullness and weight versus buoyancy. A temporary lack of control over my desire is always followed by weeks of over-control in the gym or counting calories - a negotiation and lesson in the "sin and repent" cycle that follow me into the studio and into my aesthetic.

As I inquired into longing, I discovered that I am not alone in my struggles. Reading Knapp's Appetites: Why Women Want helped me understand women's body issues in a way that no self-help diet book ever had. Knapp, an anorexic and alcoholic, understood what it was like to be controlled by the cravings of the body. She spelled out the complexities of women's appetites, addressing not only food but also sex, security, acceptance, and shopping. I saw all of those compulsions in the functional pots I was making. It seemed to solve some puzzle as to why I choose pottery as an art form. The gender aesthetics class encouraged me to question stereotypes about what is typically female or male art—an appropriate question in a field that boasts a history of male potters, yet where the domestic object is thought to exist within the realm of the female. It also introduced ideas to me about "abject art," a style that purposefully tries to be messy or grotesque in order to push viewers into understanding their own definitions of beauty, femininity, and acceptability.

In the study of female objectification we can see the ever-changing definition of beauty, represented by painters like Rubens or found in the nineteenth-century struggle between Delacroix and Ingres. Ingres's work features a sleek, almost artificial version of beauty, while in Delacroix we see a pessimistic honesty that Charles Baudelaire described as "...a hymn in praise of suffering inevitable and unrelieved." The contrast between the two painters is akin to the ceramic world's dichotomy of rough, heavily-worked pots versus slick, possibly slip-cast work. One suggests our flawed human nature, while the other is a symphony dedicated to control and technology surpassing the human hand.

In America, our relationship to food is filled with instant gratification and an unending struggle with maintaining our physical fitness. Our contemporary appetite is also having an influence over the functional objects we make. What does it mean to make pots - art about food - in a society where sixty-seven percent of Americans are overweight or obese? How does this affect a craft that has existed for thousands of years? Ceramic history shows us objects, from large ceramic storage vessels to ceremonial dishes, created so that ritual might make the event of eating more special when food was in short supply. If, as history demonstrates, functional ware is to follow societal needs, then possibly potters need to address making work for the millions of Americans on a diet.

In a recent issue of Time magazine, the history and science of appetite are explored. Through science, we've learned that we are meant to want to eat as much food as the supply will allow us. Survival was key to this, because humans were never certain when their next meal would arrive. The article goes on to state, 'We're programmed not only to overeat but also to fail to recognize immediately just when we've reached that point."* Our downfall in the West is that food has never been as plentiful as it is today. Now we must learn what no other human society has needed to: how to stop eating. This could totally change how we think about making pots and their role in our contemporary kitchens. Early on, I was taught not to make work that might compete visually with the food on a plate, because it would be off-putting to the user. Now, however, we potters have a new challenge: to make work that brings the eater into awareness of both vessel and food, while at the same time fostering appetite control.

*Jeffrey Kluger, "The Science of Appetite," Time, April 19,2007.